I had not heard from Bob since last Sunday night when I gave him a lift home after his surgery to repair a badly fractured collarbone. In this day and age of helter skelter lives and the advent of stress, folks are more reluctant than ever to “get involved.” (Let me qualify that in Bob’s case: while we assisted the fallen cyclist, perhaps a half dozen motorists stopped to ask if they could lend a helping hand.) I was not sure I wanted to become more involved in Bob’s affairs and misadventure than I already was, and so I did not bother to ask for his cell phone number (his only means of communication). His bike had been secured safely in our garage waiting to be retrieved.

Yesterday Bob and a neighbor stopped by to pick up the bike. Bob looked pretty much the same as he did when I left him, arm in a sling, his surgery dressing partially visible beyond the collar of his t-shirt. When I asked him if he was able to fill his pain medication prescription, he said, “No, I didn’t go pick it up.” “What about the pain?” I asked. “It’s been pretty intense, especially last night.” It’s been an ibuprofen routine for Bob since the surgery: three tablets every four hours. Bob said the tablets worked pretty well for the first hour. I asked him if the dressing had been changed since Sunday. “No,” he said. “The doctor gave me some post-op instructions, but I couldn’t do them by myself.” For four days he had done nothing to make himself more comfortable or insure the surgical site was clean and free of post-op infection. I noticed his little late model Ford station wagon was a stick-shift; Bob had to shift with his good hand, steer with his good arm when he needed to get behind the wheel. I was relieved to learn he’d scheduled a Dr.’s visit for this afternoon.

But all of this seemed a secondary interest to the Sarge. His main concern was the condition of his bike. He checked it thoroughly fore and aft: if the wheels tracked straight; if the shifting mechanism functioned to transfer the chain from sprocket to

sprocket. Bob checked the seat (which he had customized to fit his spare posterior). Checked the pedal action, the tension of the spokes, damage to the fork, noted all the scratches, dents, closely examined the entire machine for any other accident-caused blemishes. He went over his ride like a one-man pit crew for the Tour de France, even showed me the gash in his helmet, the spot where his head struck the pavement. Bob pointed to the dented helmet and said, “ But for this, now I’d be sitting in a nursing home somewhere with drool running down my chin.” Bob noted a slight skew to the front wheel. “The rim’s bent,” he said. “Well, I have another wheel at home.”

Home? Sunday night I discovered what “home” meant for Bob: a considerably more than “gently used” camper, and a small one at that (no sleeping compartment), surrounded by the hulks and heaps of mildewed aluminum homesteads that had probably once sat on wooden wheels. “Three Rivers Mobile Home Park,” harkened back to the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression. It was a Spartan existence Bob lived, in an ambience that Spartans, I’m sure, would have considered spartanly extreme. I will defer further description out of courtesy to Bob (nor will I post the photos I took of his “Home, Sweet, Home), but the thought that he lived a life as lean and spare as he himself (127 pounds, 5’ 6”), yet owned a bicycle worth at least two, perhaps three K, gave me some pause, I have to admit.

Upon hearing of Bob’s plight, my daughter, an empathetic and compassionate young lady, took it upon herself to research the kinds of assistance a sixty-one year old former service man (U.S. Navy) with no health insurance and a busted collarbone could fall back on should his situation require it. She contacted the Snohomish County Senior Citizen Assistance program and learned of several services Bob might avail himself of should he choose to do so.

The informational packet arrived in yesterday’s mail. Around ten a.m. this morning I hand delivered the packet to the trailer park and Bob’s camper. He answered my knock and I handed him the packet, which he opened immediately. I had included a personal note in case I found no one at home, apologized for “meddling,” but had done so only out of my concern for him and his situation. I was relieved when he said, “You’re not meddling; I appreciate your help but I’m not a senior citizen.” “Well……..,” I said, and nodded an affirmative. I told himI had forgotten to hand him the material the day he stopped by for the bike and to feel free to do what he wished with the material. “I’m pretty independent,” he remarked. Yes, I thought, but “independent” don’t chase away the pain.

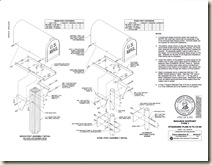

We stepped outside into the pungent smell of cat feces and urine. “Let me shut the door,” Bob said. “I don’t want the mosquitoes to get in.” We discussed the invention he has staked his scant bankroll on: a sensor that measures tolerances to micro-distances, one he hopes to peddle to the airline industry. “If it ‘flies,’” he said, “I’ll be able to buy my own jet!”The testing phase begins in Lynnwood next week .

The mosquitoes had discovered us by now, droning away as they maneuvered to slip in under our tolerances. A dog tethered to the trailer next door yapped incessantly. I heard a shout, not a gleeful shout, but angry, tinged with a frustration bordering on….despair, perhaps? “Good luck with the sensor,” I said. “Life’s like an elevator,” Bob replied and smiled his Spartan smile: “Sometimes it takes you up; other times you get the shaft.” I shook his hand, glanced at his bandaged shoulder, once more at the dilapidated little camper that was his present life, and as I returned to my truck, weaving my way carefully between the sand-encrusted piles of cat droppings, I felt I pretty much knew where Bob’s next elevator ride would take him.