H.D. Thoreau, Walden

Pussy willows are budding in the Valley again. Four years ago on this date pussy willows ushered in the first post of The Valley Ripple. It seems appropriate, then, for The Ripple to exit four years from that day in pussy willow time. Effective this post The Valley Ripple is on indefinite hiatus.

This farewell post is The Ripple’s three hundredth: 300 posts to cover four years in the life of the Tualco Valley. When I posted my first post February 19, 2010, I had no idea what I was in for. I knew very little about blogging or the work that went into creating a satisfactory post. I was entirely unprepared for the amount of time it takes to compose a post. I won’t belabor the process but suffice it to say, a post does not just roll off one’s fingertips. Blogging, I soon discovered, is a time intensive activity. Not only must the writer take an idea in its “raw” form and round it out, but then there’s the formatting of images, which after they’re taken, must be transferred from camera to computer and then inserted into the post. This is not a complaint, but an explanation, rather, of part of the process. For me, though, I would be denying the truth if I didn’t admit that writing The Ripple was not only a gratifying task, but great fun, as well.

So why stop the presses, you ask? The time element certainly, but to some degree this blogger experienced “performance anxiety,” too: you feel compelled to create regular posts (I tried for at least one a week), and posts you could take pride in, also. But the main reason—and I refer to this post’s opening quote from Thoreau’s Walden—I have other “lives to live,” other writing projects I want to move on to. In short, I have reached my destination and it’s time to plan a new trip. For four years now I’ve been the Valley’s online advocate. It’s time to move on.

But before The Ripple goes silent, let me share some observations about my blogging experience. Writing is a mental activity, and The Ripple allowed me the luxury of playing around with words, stringing them together in sentences, revising those words, moving text around to where it best fit.

Each post was an adventure: even though I had an idea or item of news at the outset, I was never quite sure where it would lead me. More often than not, where I ended up was a complete surprise. A post takes on a life of its own: you follow its lead, are bewildered often at the journey, but when it ends…oh, so satisfying!

300 posts. Knowing I have a penchant for the verbose, I’ve wondered just how many words comprised The Ripple over the last four years. To rein in my wordiness, I often checked the “word count” function of my blog program. (A writer once explained why it took him longer to write a book than planned. His reason? Deciding which words to leave out.) In spite of all the editing and revising that went into each post, try as I might, I always seemed to add words to the total. I was aware some posts droned on interminably, but let me give you some perspective on word count. Three hundred posts at, say, an average of a thousand words per post (some longer, some shorter): apply a bit of simple math and that gives The Ripple a word count of three hundred thousand and some odd (yes, in some cases, “odd”) words. Round it up to 310,000 just to be generous. 310,000 words for four years worth of blogging. That’s a whole lot of reading material, you say. Here’s the perspective: Count Leo Tolstoy’s four volume (plus Epilogue) epic novel War and Peace contains, depending on who’s counting, between 500,000 to 600,000 words in English translation (and Sonja Tolstoy hand copied the manuscript seven times—there’s true love for you). At least The Ripple had pictures!

On a more serious note, one more observation. Under the veneer of Valley civility I’ve discovered there are frictions, small ones, a slight grazing of elbows. And this is my only comment: we can and need to be better neighbors here in the Valley.

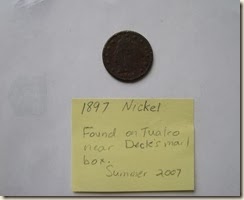

Even a blog must have its acknowledgements. Not only did blogging give me a good mental workout, it also provided considerable open-air exercise several times a week, either on foot or chugging through the Valley on my faithful vintage 1976 Tourist II Columbia three-speed bike, Gladys. And thanks to Gladys, too. Without her help I would not have been able to gather the news from all four corners of the Valley.

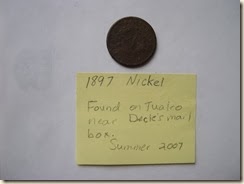

Thanks to The Ripple, I was able to meet new neighbors and become better acquainted with the old. Also, the constant search for news brought me in contact with many colorful non-residents who visit the Valley for all sorts of reasons. I thank them for their interest and the variety they gave my posts.

Those who followed The Ripple faithfully, read, shared information and commented on the posts, I thank you, too, for your involvement and encouragement. The Ripple was all the better for them.

And last of all, thanks to the Tualco Valley. For the editor, it has been and will continue to be a place of inspiration, a place for reflection, a place of quiet wonder.

Tualco has its routines and they will continue. But the Valley is not static: there is always something new, something unique, something of interest. And ideas and musings seem to jump out at you. And I’ll continue to have my eyes on the Valley; any news will be added to the archives. But for now, a long rest and pleasant dreams to The Ripple…and neighbors, when we pass each other in the Valley, let’s keep exchanging those smiles and friendly waves, for neighbors we are and neighbors we’ll continue to be….

The Editor

(Let The Ripple correct an egregious oversight. As is often the case in the Academy Awards where the recipients thank all those without whose assistance they would never have reached the pinnacle of achievement represented by the golden icon they hoisted triumphant as they left the stage, some essential personage, (most often a spouse), is shamefully omitted from their glowing acknowledgements. While The Ripple was never in the running for the Edward R. Murrow Award for Journalism, nonetheless it owes a debt of gratitude to those who tirelessly worked behind the scenes whenever research was asked of them. Thus, with the sincerest of apologies, the editor wants to recognize its faithful and devoted research staff for the many long hours it spent to insure The Ripple got it right.

The Editor (crestfallen)