Without a taste of water…

Cool, clear water.

Old Cowboy Western tune

Going into Fred Meyer’s the other day, I passed a man exiting the store, his cart heaped to the brim with cases of bottled water. Just inside the door two or three customers were lined up at the fresh water kiosk. I’ve since read that east of here one of the two wells that supplies water to the little town of Startup has gone dry. I cross the Skykomish River almost daily and these days it appears more bed than river. Where there used to be swimmers, there are now waders. Everett, Seattle, and Tacoma have issued voluntary water conservation measures, urging their customers to cut back on daily water usage ten percent. All this because our endless summer has been a rainless one, and with last winter’s snowpack less than ten percent of normal, our rivers will only dwindle, become creeks, trickles even.

I can only remember one similar summer in the forty years we’ve lived here, but I also recall more rain that season during the “dry months” and though the preceding winter’s snowpack was subnormal, it was not ninety percent below normal. Usually water issues here in the Valley stem from an excess of the stuff not a dearth of it, especially the late fall months when some years past during the night I’d rise hourly and cross the road, flashlight in hand, to see what Riley Slough was “up to.”

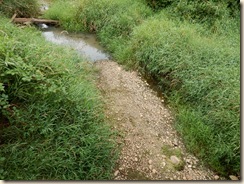

And crossing the lower Loop Road over the bridge just two days ago where I normally see a great blue heron, knobby knee deep, or a pair of ducks, (and last summer a busy beaver),… where usually the marsh grasses ebb and flow in the gentle current like a sea hag’s hair, and minnows dimple the surface, I glanced down and was shocked to see a strange sight: Riley’s bottom. Yes, a small gravel bar, surrounded by pools and puddles, is all that currently (or should that be “current less?”) remains of Riley Slough at the crossover. No fish crossing or spawning there this fall; scarcely enough water to wet a minnow.

When the waters are parted, or in Riley’s case, dried up, oftentimes long lost civilizations emerge. Lake Mead’s drought subsidence has yielded up three submerged ghost towns, allowing the ghostly residents to wring the water from their sheets for the first time in years. When our state’s Wanapum Dam on the Columbia was found to have a crack in its spillway, repairs required the reservoir to be drawn down twenty-six feet, a subsidence that left structures submerged for fifty-two years high and dry. (That old swing set the glider component of which nearly crushed my fingers must still be rusting away forty feet below the surface of reservoir behind Douglas County’s Wells Dam Hydroelectric Project.) Hoping to see some long submerged artifact, I peered over the railing at Riley’s bottom but instead of an ancient native firepit or moccasined footprint, I saw nothing but rocks and gravel.

Just last weekend I watched a segment about water on CBS’s “Sunday Morning.” The piece highlighted a Navajo Indian Reservation in New Mexico. None of the “rez” residents have running water in their homes. Within the reservation’s borders there is only one well with potable water. Navajo with vehicles drive upwards of fifty miles one way to fill five gallon buckets with water then drive the fifty miles back with their water ration. Navajo who don’t own vehicles obtain their water from the Reservation’s sole water truck which because of the territory and families it serves delivers water once a month. That delivery of two to three fifty gallon barrels per stop must last a family until the next delivery. I saw a family of four—grandmother, mother, and two grandchildren—wash their hair in a plastic tub, each using the same water so as not to waste a drop. The reservation is not without other wells, but the Navajo who drank from them became ill from contaminated water, residue from uranium mining of the 40’s and 50’s. Hydrologists believe aquifers 600 feet underground are also rife with pollutants. Deeper wells are needed but there’s the cost (always the cost): the state and county believe it’s the Fed’s responsibility to foot the bill for deep wells; the Fed passes the buck back to the state…states’ rights, you know… the state's responsibility. I think of our great republic where the average American uses 100 gallons of water a day while on American soil descendants of our indigenous peoples—and the WWII Code talkers-- as if they were a 3rd World Country people, must share the same water to wash their hair.

…Where the water’s running free,

and it’s waiting there for you and me,

cool, clear water… (same old western tune)

As Gladys and I wobbled home, I saw the Valley under serious irrigation: the dairies’ big manure sprinklers spraying clear water on the hayfields, Willie Green’s acres of leaf crops drinking up the water from irrigation pipelines, sprinklers going in chard and kale fields (saving our food, my brother says), and Van Hulles’ pastures. I think about a conversation I had with Shay Hollander who floated the Sky from the first launch site on Ben Howard Road. Shay said it took his party nearly three hours to float to Monroe, twice the normal amount of time. I think about our shallow water table and drilled well which has delivered like “Old Faithful”for forty years—only twenty-seven feet deep. (Our old dairy farmer neighbor Herman Zylstra witched our well and when Rob Aurdal drilled it, Herman urged him to drill another four to five feet deeper. “Don’t need to,” Rob replied. “They’ll have all the water they need right here.” And with that, Rob packed up his drilling rig and drove off into the sunset. Old timers have told us we’ll not lack for water as long as there’s water in the Sky. But now waders are crossing the river at will and river bars used to rushing current bask exposed in the ninety degree heat. I’m not saying I want to be on flood watch hour on the hour. But I would like to wash my hair more than once a month. There’s not much of it left. Just a few drops of water is all I'd need… a few drops of cool, clear water.

He’ll hear our prayer

And show us where there’s water,

Cool clear water

( there’s that old tune again…)