The sweet peas loose their fragrance

On the Valley air.

I can’t imagine a summer garden without sweet peas.

The sweet peas loose their fragrance

On the Valley air.

I can’t imagine a summer garden without sweet peas.

“Yes, I can bake a cherry pie,

Quick as a cat can wink his eye…”

“Are the leaves turning already?” I wonder as Gladys and I spin along Tualco toward the Barrell Man’s house. I’m referring to a tree in his backyard. Then I realize it’s mid-July and those aren’t leaves blushing red on the tree, they’re pie cherries, and a bumper crop, too. Last summer I stopped by with bartering on my mind: a quart of Valley honey for enough pie cherries to fill a pie crust. The Barrell Man was kneeling among his corn rows plucking weeds. I noticed right away the backyard cherry tree had only a sparse setting of fruit. We chatted a while but because of the scarcity of cherries, I made no mention of a possible exchange of honey for cherries.

At one time we had two backyard cherry trees. One spring some sort of beetle infested both. I noticed tiny holes oozing sawdust from the trunks; each tree looked like it had been shot-gunned. A good dousing of the trunks with insecticide came too late: the younger tree died and the older, badly damaged, never recovered. Two years later I cut it down, yanked the stump, and for years there were no fresh cherry pies made from our backyard cherries.

Two years ago I purchased a bare root Montmorency pie cherry tree and planted it where its predecessors once stood. To prevent the return of those tree boring beetles, in late March I use an oil-based dormant spray and apply it liberally to trunk and branches. The tree yielded a handful of cherries its first year. This spring the little

“Monty” had a heavy bloom and I had high hopes my close attention to its health would provide enough fruit for one cherry pie.

May came and the tree’s flower stems began to show green pips. June. The pips had swollen and turned yellow. It’s hard to judge just how many cherries, when picked and pitted, would amount to four cups of fruit, but I was determined to make a pie—even if it was a miniature eight inch. No, I would not settle for a cobbler. On that point I was determined.

July. The cherries, now plump little morsels, had turned a uniform deep red. They dangled from their stems like ruby pendants, and though I was tempted to pluck a few to eat fresh, I held off; this first crop was destined to become a pie.

Harvest time. I rounded up a picking bucket and headed out to fetch my pie. Carefully I removed the netting; there was not a single cherry to spare. Off with the fruit, one stem at a time. Tree-ripened and fresh, that’s how I wanted the cherries. With visions of pie slices in my head, I cleaned the tree of every single cherry. As the bucket filled, I weighed my pie chances. I had hopes that eight inch pie might just become the standard nine. With the harvest and my hopes in the bucket I headed for the house.

* * * *

While the oven is warming, allow me a strange digression. The topic? Evolution--specifically the evolution of Man. More specifically yet the evolution of Men. I’m talking about two innovations that have brought us men out of our stone age caves into the light of the modern age, brought us out of the dark woods of hunting and gathering, moved us males along the evolutionary trail from Homo ineptness a few steps closer to Homo capabilis, two miracles of modern times that have brought us more on par with the nimble fingers and knack for the creative that are the hallmarks of the females of our sex.Two giant steps for menkind indeed when the gift bag and Ready-Made piecrust came along.

The gift bag. When the time comes for us men to wrap a gift for that special someone, no longer do we need wish we had four hands to tie the bow. No longer do we need to take Origami 101 to learn how to swaddle a gift in wrapping paper, graft the thing together with a minimum of cellophane tape; no longer be uncertain if we’ve taped the right seams, allowed enough wrap to cover the gift; in short, come up with package that shows some creativity and is pleasing to the eye of the recipient, rather than a jumble of paper, tape, tags, and bows that looks as if a young child or chimpanzee collaborated on the thing. Just select a bag large enough to hold the gift, is season-appropriate, and a festive color. Certainly we men are up to that task. Just pop the gift in the bag and discretely cover it with colorful, loosely wadded sales fliers. (The more evolved among us might even select matching colored tissue paper.) There’s your gift--all tastefully presented and with little handles to boot!

Ready-made piecrust. Man crust, I call it. Remember Simple Simon of nursery rhyme lore (“Simple Simon met a pieman going to the fair…”)? I just suspect Mrs. Simon baked the pies; Mr. Simple was simply the salesman. Now, guys, piecrust comes in a box, conveniently rolled up for the man who himself would bake pies. No muss or fuss with that troublesome dough, the cutting in of shortening, lard, butter (decisions, decisions…). No more do our clumsy hands have to fumble a dough roller and try to smooth out a crust that’s not an ellipse, or a trapezoid, or a square (a square crust in a round pan??) and fractured around the edges. Just slip a Ready-Made out of its sleeve, unfurl it, and there it is in all its perfect rotundity.

I squeezed just enough fruit from this year’s cherry crop to fill a nine inch pan: a tad shy the four cups of fruit the recipe called for. A few more cherries would have been nice; where pies are concerned, it’s better to have extra filling than not enough. Nobody likes a pie with sparse innards—not this pieman anyway. Not having the burdensome task of trying to meld flour, shortening, and water into a suitable receiving blanket for pie filling allows one to express his creativity with the other ingredients. In my case, switching out the flour as a thickening agent for tapioca instead. A fruit pie isn’t complete without those little translucent globules of manioc buds to glue the works together. (This pieman also doesn’t like his slice of pie to juice out in the pan, sending him to the silverware draw in a huff for a serving spoon to ladle the leaked contents sauce-like over the deflated slice.)

In goes the filling. Next, pats of butter enough to impress Julia Childs and you’re ready to marry top and bottom crusts.

A half hour later. The smell of pie success fills the kitchen. A few minutes more and I’ll lift a nicely browned, bubbling pie from the oven; the two-year old tree will have provided its first pie. Next year it’ll surely yield more. I might even make a cobbler.

The highway noise increased further a half dozen years ago when the DOT ground a rumble strip down the center of 203. Thereafter, whenever a distracted driver wandered over the centerline, it sounded like a burst of automatic weapons fire outside. And that straightaway again, a passing opportunity waiting to happen. You heard an engine wind up, a burst of weapon’s fire as the vehicle crossed into the oncoming lane, and you held your breath waiting for the answering fire as the passing car reentered the right lane. I’m sure I’ve mentioned also in an earlier post the country bumpkin hay truck driver who for reasons that remain a mystery to me, compression brakes through all eighteen gears starting at Duvall and grinds to halt to negotiate the left turn on Tualco heading for the dairy farms.

Five a.m. this morning and I’m awakened by a helicopter hovering nearby. And hovering, and hovering…. It’s not one of those little dragonfly ‘copters that fly over with a tolerable insect-like hum either. This chopper is most likely a news aircraft like Chopper 7. I know it’s not a Medi-Vac craft because they’re fast flying, urgently roaring in and out of the Valley. Hardly a chance I could return to sleep with that thing droning away overhead. Besides, a news helicopter…must be something going on: a river accident, a traffic issue on Highways 2 or 522, police activity in Monroe, a fire…. I crawl out of bed, pull on some shorts, and head for the backyard to investigate.

The sky was filled with helicopters…well, three anyway, all circling the prison area. An escapee, perhaps? Another tragedy involving a corrections officer? A riot? (I recalled a riot at the facility in the ‘70’s. I heard the news as I was on my way home from Snohomish on Highway 2. As I approached town, an eerie feeling came over me when I saw a plume of dark smoke drifting above the prison complex. Who knew what destruction was taking place there! The drive took much longer than usual because I had to slow and move to the shoulder several times to allow State Patrol and Sheriff’s cars rushing to the fray speed by. If memory serves, the riot continued for several hours before it was quelled.)

As the ‘copters continued their clattering overhead, I went into the house and switched on the morning news to discover just what it was that brought helicopters from all three local t.v. stations choppering their way to Monroe. What disaster, catastrophe or tragedy had struck our peaceful town? “Breaking News” flashed across the screen and an aerial view of the prison flickered into view. What was it? Oh, no! Something was happening at the prison! The grounds seemed calm and orderly, though. No swat teams, no phalanx of police in riot gear, no emergency vehicles, flames, smoke…. No, none of that routine stuff. “Breaking News” was REAL, riveting news this time. A solitary bobcat (a cougar, perhaps? Even greater REAL news…) had somehow strayed onto the complex, (was Copper River salmon on the prison’s luncheon menu?), was startled into the razor wire and in freeing itself, received a cut on its leg. Groundskeepers called a vet who tranquilized Kitty Bobcat and transported the injured feline to the his office to stitch up its wound.

The big kitty will be fine, I’m sure. As for me, the adrenalin’s worn off, my breath has returned, heart rate back to normal. Suddenly I realize I’m tired, once again sleep-deprived here in the Valley. I’m sorely in the need of a nap before lunchtime. But not to worry: Cadman’s boom at high noon will keep me from oversleeping.

Is worth a ton of hay.

A swarm in June

Is worth a silver spoon.

A swarm in July

Isn’t worth a fly…

Beekeeper’s proverb

Last week I was about to fire up the lawnmower and begin the afternoon’s chores when I discovered the air was full of bees. A swarm had issued from a colony I thought most unlikely to engage in that sort of behavior because I had made a nice split from it a month and a half ago.

A honeybee swarm is a winged miracle, and excepting the Biblical plague of locusts, is perhaps the greatest wonder of the insect world. I’m sure to the uninitiated, finding oneself in the midst of a swirling, roiling mass of stinger-bearing insects seems a horrific nightmare. Granted, a swarm of armed insects invading human airspace is not the best PR for the embattled honeybee. The bees’ PR image was further damaged in 1978 when Hollywood sensationalized the appearance of the Africanized honeybee in the contiguous United States by releasing the disaster film The Swarm, the insect equivalent of Hitchcock’s The Birds. But ask any keeper of bees and he will testify that being in the presence of a healthy swarm is a phenomenon that is a source of constant amazement.

If one keeps bees for their honey, timing is important. In our short season Pacific Northwest, good timing is particularly so. Berries, especially wild blackberries, are the summer’s main nectar source in the Valley. As I write this post, the blackberry is in full bloom and the conditions for a nectar flow—consecutive warm, dry days with longer periods of daylight—are the best I’ve seen since 2009. Each blossom’s nectaries are brimming with nectar.The last thing this beekeeper needs in early July is to have a strong, honey producing colony spin off half its field force and send it flying away on summer vacation; it’s poor timing when half your work force decides to go house hunting just as harvest shifts into full swing. That’s why, though impressive as it was, my honey hopes sank when I saw that pulsing amoeba of bees heading west toward the horizon. As the old beekeeping saw states, a swarm in May (“worth a ton of hay”) or June (“worth a silver spoon”) means it yet has time to establish itself and still produce a season’s surplus for the beekeeper. In July in our short season fickle weather Valley when a honey flow of only two weeks is more the rule than exception, a swarm (“isn’t worth a fly”)—unless the beekeeper’s goal is to raise bees, not collect honey, especially when Valley honey commands a premium price of over six dollars a pound.

Swarming is the honeybee’s insurance that its species will perpetuate. Overcrowding shifts the colony into swarm mode. The queen bee’s role is to lay eggs and this she’ll do to the tune of 1,000 a day. When the brood chambers are clogged with larvae, the queen has nowhere to lay. Because that’s her job, her attendant bees aren’t about to let her lie around and draw rocking chair (the drones’ job), so they select certain larvae two to three days old (each worker egg is a potential queen bee) and begin feeding them a royal diet. A strong colony may rear nearly two dozen new queens; only one, however, will be the next claimant to the colony’s vacant throne. Shortly before the new queens emerge fifteen or sixteen days later, one-third or more of the bees and the old queen will swarm from the colony and rise together in a cloud. The entire mass rotates much like a hurricane with the queen as its eye and slowly swirls off. This is the first time the old queen has been outside the hive since her mating flight.

What happens to the bereft parent colony when a good portion of the hive has flown the coop? A new queen will take command, surely, but again consider the workings of the honeybee hive: the virgin queen must take her mating flight before she’s fertile; it will be four or five days, weather permitting—before she lays her first fertile egg. That egg and its successors will not become adults for twenty-one days…nearly a month’s interregnum before any new blood arrives to bolster the hive. A honey flow of two to three weeks? There’s that timing issue again.

Beekeeping lore has it that the beekeeper can encourage a swarm to settle by banging on pots and pans. Also spraying water on the swirling bees supposedly brings them quickly to earth. This beekeeper has never tried either method because I’m too intent on watching where they go to run to the pantry or uncoil the water hose.

At this point in the post I want to reassure those who panic at the thought of being in the vicinity of a swarm of bees. Honeybees are most passive in the swarm mode; they are suddenly gypsies, have no hive to protect, and like the Boll Weevil song, they’re “just lookin’ for a home”; you are the last thing on their little bug minds. Impressive…yes, they are indeed. A threat? By no means.

The mass of bees poured into the air, circling around the queen. Once airborne, they became a loosely swirling ball taking up several feet of airspace.

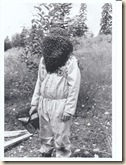

This swarm slowly moved west, sifted around, through, and over the lilac bush, on beyond the woodshed. The swarm stalled by the walnut tree and the bees began spilling out of the air and rained down on a low branch eight feet or so off the ground. The queen has landed. Five minutes later the branch was laden with twenty-five to thirty thousand worker bees plus her Royal Highness. The swarm was huge, one of the largest I have ever seen in all my years keeping bees. Seven pounds of them by my estimate in a cluster three feet long and a good drooping foot at the sag.2:00 p.m. and the swarms sways there like Mrs. Greaves’ underarms when she played “Dry Bones” for our eighth grade sing-a-long sessions. Tomorrow I’m heading out of town. What do you do, then, with a swarm that’s “not worth a fly?” You consider the beekeeper’s motto, that’s what you do: “Wait until next year.” Yes, you look ahead to next year’s honey crop (usually because nothing’s happening with this year’s). Or you can yet save the day—or the season—by hiving the swarm, wait a week for it to establish itself, and then combine it with the parent colony. The stronger queen will prevail and your workers are no longer on strike and will soon return to work plundering the blackberry blossoms; you’ve lost a week, but may salvage the season.

As to its hiving, each swarm is unique and requires some thought as to how one should set about capturing it: a swarm on a low branch is not the same as one dangling forty feet up in a fir tree (I don’t do that anymore, ladies; sorry, you’re on your own). A swarm on a fencepost, a much different approach. On the windshield of a car? Wipers won’t be of much assistance. On your head? Well, that takes some thought, as well. And the shape of the cluster becomes a consideration, too. Years ago someone gave me a nylon mailbag I have used a number of times to capture sock-like swarms. Just slip it like a sleeve—or sock—gently up around the swarm, tie it off at the top, lop off the limb and carry home your prize to hive at your convenience. Logistics of this swarm rendered the mailbag useless. The swarm clung to a branch nearly two inches in diameter, seven feet in from the tip. If I tried to saw through the limb, the branch, characteristic of walnut, would snap, tumbling the entire works to the ground. No, this configuration required shaking. Two stepladders, two 2”x 4”s stretched between, with the receiving hive positioned underneath the swarm…a good shake of the branch and down they’ll come into the box. That should do the trick. The fact the bag of bees was slightly longer than the receptacle…well, I’d box the majority, and the queen was certain to be with them. The spillage would quickly make their way to Mama. In the meantime I readied the receiving hive, placed it on the ground nearby. I could set the ladders later.

6:00 p.m. Out I went to prepare the scaffolding, set the empty box strategically under the now huddling cluster, and prepare to retrieve my wayward bees. I complimented myself on adding one more hiving experience to the years of swarms that came before. A silent boast, too, about the ease with which I’d capture the bees. A well-laid plan, I thought, a surefire cinch to work. I had everything I needed: the means to reach the bees, an empty hive and years of experience with this kind of thing. I had everything going for me, I thought, as I approached the capture zone. I had everything…except the bees! The branch where an hour before they sagged by the thousands was bare. Nothing but twigs, leaves and bark. I could hardly believe my eyes. Every last one of them had sailed off into the sunset. No ton of hay, no silver spoon—nothing but a barren branch not worth a fly. Bewildered and seven pounds of bees poorer, I slowly made my way back to the house trying to console myself with: “Oh, well, wait until next year.” But next year seemed a very long way off.

There is always somewhere a weakest spot,--

In hub, tire, felloe, in spring or thill,

In panel, or crossbar, or floor or sill,

In screw, bolt, thoroughbrace,—lurking still,

Find it somewhere you must and will,…

The Deacon’s Masterpiece

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Gladys is old. Nor was she a spring chicken when our paths crossed years ago. In fact Gladys is a vintage Columbia bicycle (“Roll on, Columbia, Roll on…,” 3/2/2010 ) and I know it’s not considered gentlemanly to reveal a lady’s age, but let me say if I were to fire up a birthday cake, present it to her in the garage, she would bask in the glow of thirty-seven candles. As Gladys and I roll along, we are a parade of the ages, a combined one hundred five years wobbling our way around the Loop.

Each time we head on down the road, it’s always with a tinge of uneasiness on my part. As we all are, Gladys is the sum of her parts. She’s a mechanical being, Gladys is. Things mechanical break down, wear out, fall apart. The covenant between us, Gladys and me, is that she won’t fall apart at the point of no return, leaving me to plod the long road home.

A half dozen years ago in addition to Gladys’s usual wheezing, I noticed strange tinkling noises coming from my vintage Columbia. Whatever your mode of transportation, you are in tune to the sounds it makes and if these in any way vary, it does not bode well and usually means a trip to your friendly mechanic is in order. I squeaked to a halt just a stone’s throw from the Lower Loop bridge (one quarter mile from the point of no return) and hopped off to check out the problem. The chiming, I discovered, came from a number of broken spokes on the front wheel. With every revolution of the wheel the loosed spokes would jangle against their fellows, thus the tinkling sound. I held my breath she’d hold up until we returned home (no easy thing to do when you’re pedaling an old classic).

At home, after a futile attempt to reconnect and tighten the spokes failed, I upended Gladys, removed her front wheel, and headed for the bike shop in town. Just a matter of replacing the spokes, I thought. Things mechanical are always complicated; the shopkeepers tell me they can’t fix the wheel, had no replacement for it, and would have to order a new one. I’d be afoot, I’m told, for at least two weeks.

In the Valley last August I met Eric Benshoof and his bad boy vintage Harley, Snedley. The “Collector” license plate started us talking about the ages of our respective rides. That led to a little research into Gladys’s history. I contacted the Columbia Bicycle Manufacturing Company in Westfield, Massachusetts, and straightaway noticed a bit of disconcerting information on their home page: something to the effect they have no parts inventory for vintage Columbia’s and recommended eBay or Craig’s List as good sources to look for replacement parts. I accessed the site’s “contact us” button and after an email or two from Lisa, I learned Gladys was a Tourist 3 bicycle (“3” for three-speed, I assume) and was manufactured in 1975. (Gladys, then, predates Snedley by two years.) All this serves to reiterate Gladys is a classic, and classics are especially prone to mechanical failure. I’m certain, capricious as the old lady is, one day she’ll leave me afoot at the far end of our route…most likely when I’ve an appointment to keep or some time-sensitive obligation to meet.

The other day I heard some news that takes a bit of pressure off my Valley rides, lessens my fear somewhat that one day I’ll be left afoot in the vicinity of the stop sign where the Lower Loop road connects with the upper. The Triple-A organization announced it has extended its coverage to include not just motorists but bicyclists as well. Now I’ve been a card-carrying member of AAA for years and have yet to use their roadside assistance services. AAA’s coverage extends to classic cars and motorcycles, so why not vintage bicycles, I ask? That means, of course, in addition to hauling my camera and pepper spray canister, I’ll now have to pack a cell phone, too.When you ride a classic, it’s not a matter of if, but where and when.