Is worth a ton of hay.

A swarm in June

Is worth a silver spoon.

A swarm in July

Isn’t worth a fly…

Beekeeper’s proverb

Last week I was about to fire up the lawnmower and begin the afternoon’s chores when I discovered the air was full of bees. A swarm had issued from a colony I thought most unlikely to engage in that sort of behavior because I had made a nice split from it a month and a half ago.

A honeybee swarm is a winged miracle, and excepting the Biblical plague of locusts, is perhaps the greatest wonder of the insect world. I’m sure to the uninitiated, finding oneself in the midst of a swirling, roiling mass of stinger-bearing insects seems a horrific nightmare. Granted, a swarm of armed insects invading human airspace is not the best PR for the embattled honeybee. The bees’ PR image was further damaged in 1978 when Hollywood sensationalized the appearance of the Africanized honeybee in the contiguous United States by releasing the disaster film The Swarm, the insect equivalent of Hitchcock’s The Birds. But ask any keeper of bees and he will testify that being in the presence of a healthy swarm is a phenomenon that is a source of constant amazement.

If one keeps bees for their honey, timing is important. In our short season Pacific Northwest, good timing is particularly so. Berries, especially wild blackberries, are the summer’s main nectar source in the Valley. As I write this post, the blackberry is in full bloom and the conditions for a nectar flow—consecutive warm, dry days with longer periods of daylight—are the best I’ve seen since 2009. Each blossom’s nectaries are brimming with nectar.The last thing this beekeeper needs in early July is to have a strong, honey producing colony spin off half its field force and send it flying away on summer vacation; it’s poor timing when half your work force decides to go house hunting just as harvest shifts into full swing. That’s why, though impressive as it was, my honey hopes sank when I saw that pulsing amoeba of bees heading west toward the horizon. As the old beekeeping saw states, a swarm in May (“worth a ton of hay”) or June (“worth a silver spoon”) means it yet has time to establish itself and still produce a season’s surplus for the beekeeper. In July in our short season fickle weather Valley when a honey flow of only two weeks is more the rule than exception, a swarm (“isn’t worth a fly”)—unless the beekeeper’s goal is to raise bees, not collect honey, especially when Valley honey commands a premium price of over six dollars a pound.

Swarming is the honeybee’s insurance that its species will perpetuate. Overcrowding shifts the colony into swarm mode. The queen bee’s role is to lay eggs and this she’ll do to the tune of 1,000 a day. When the brood chambers are clogged with larvae, the queen has nowhere to lay. Because that’s her job, her attendant bees aren’t about to let her lie around and draw rocking chair (the drones’ job), so they select certain larvae two to three days old (each worker egg is a potential queen bee) and begin feeding them a royal diet. A strong colony may rear nearly two dozen new queens; only one, however, will be the next claimant to the colony’s vacant throne. Shortly before the new queens emerge fifteen or sixteen days later, one-third or more of the bees and the old queen will swarm from the colony and rise together in a cloud. The entire mass rotates much like a hurricane with the queen as its eye and slowly swirls off. This is the first time the old queen has been outside the hive since her mating flight.

What happens to the bereft parent colony when a good portion of the hive has flown the coop? A new queen will take command, surely, but again consider the workings of the honeybee hive: the virgin queen must take her mating flight before she’s fertile; it will be four or five days, weather permitting—before she lays her first fertile egg. That egg and its successors will not become adults for twenty-one days…nearly a month’s interregnum before any new blood arrives to bolster the hive. A honey flow of two to three weeks? There’s that timing issue again.

Beekeeping lore has it that the beekeeper can encourage a swarm to settle by banging on pots and pans. Also spraying water on the swirling bees supposedly brings them quickly to earth. This beekeeper has never tried either method because I’m too intent on watching where they go to run to the pantry or uncoil the water hose.

At this point in the post I want to reassure those who panic at the thought of being in the vicinity of a swarm of bees. Honeybees are most passive in the swarm mode; they are suddenly gypsies, have no hive to protect, and like the Boll Weevil song, they’re “just lookin’ for a home”; you are the last thing on their little bug minds. Impressive…yes, they are indeed. A threat? By no means.

The mass of bees poured into the air, circling around the queen. Once airborne, they became a loosely swirling ball taking up several feet of airspace.

This swarm slowly moved west, sifted around, through, and over the lilac bush, on beyond the woodshed. The swarm stalled by the walnut tree and the bees began spilling out of the air and rained down on a low branch eight feet or so off the ground. The queen has landed. Five minutes later the branch was laden with twenty-five to thirty thousand worker bees plus her Royal Highness. The swarm was huge, one of the largest I have ever seen in all my years keeping bees. Seven pounds of them by my estimate in a cluster three feet long and a good drooping foot at the sag.2:00 p.m. and the swarms sways there like Mrs. Greaves’ underarms when she played “Dry Bones” for our eighth grade sing-a-long sessions. Tomorrow I’m heading out of town. What do you do, then, with a swarm that’s “not worth a fly?” You consider the beekeeper’s motto, that’s what you do: “Wait until next year.” Yes, you look ahead to next year’s honey crop (usually because nothing’s happening with this year’s). Or you can yet save the day—or the season—by hiving the swarm, wait a week for it to establish itself, and then combine it with the parent colony. The stronger queen will prevail and your workers are no longer on strike and will soon return to work plundering the blackberry blossoms; you’ve lost a week, but may salvage the season.

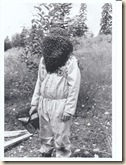

As to its hiving, each swarm is unique and requires some thought as to how one should set about capturing it: a swarm on a low branch is not the same as one dangling forty feet up in a fir tree (I don’t do that anymore, ladies; sorry, you’re on your own). A swarm on a fencepost, a much different approach. On the windshield of a car? Wipers won’t be of much assistance. On your head? Well, that takes some thought, as well. And the shape of the cluster becomes a consideration, too. Years ago someone gave me a nylon mailbag I have used a number of times to capture sock-like swarms. Just slip it like a sleeve—or sock—gently up around the swarm, tie it off at the top, lop off the limb and carry home your prize to hive at your convenience. Logistics of this swarm rendered the mailbag useless. The swarm clung to a branch nearly two inches in diameter, seven feet in from the tip. If I tried to saw through the limb, the branch, characteristic of walnut, would snap, tumbling the entire works to the ground. No, this configuration required shaking. Two stepladders, two 2”x 4”s stretched between, with the receiving hive positioned underneath the swarm…a good shake of the branch and down they’ll come into the box. That should do the trick. The fact the bag of bees was slightly longer than the receptacle…well, I’d box the majority, and the queen was certain to be with them. The spillage would quickly make their way to Mama. In the meantime I readied the receiving hive, placed it on the ground nearby. I could set the ladders later.

6:00 p.m. Out I went to prepare the scaffolding, set the empty box strategically under the now huddling cluster, and prepare to retrieve my wayward bees. I complimented myself on adding one more hiving experience to the years of swarms that came before. A silent boast, too, about the ease with which I’d capture the bees. A well-laid plan, I thought, a surefire cinch to work. I had everything I needed: the means to reach the bees, an empty hive and years of experience with this kind of thing. I had everything going for me, I thought, as I approached the capture zone. I had everything…except the bees! The branch where an hour before they sagged by the thousands was bare. Nothing but twigs, leaves and bark. I could hardly believe my eyes. Every last one of them had sailed off into the sunset. No ton of hay, no silver spoon—nothing but a barren branch not worth a fly. Bewildered and seven pounds of bees poorer, I slowly made my way back to the house trying to console myself with: “Oh, well, wait until next year.” But next year seemed a very long way off.

Print this post

No comments:

Post a Comment