Oscar Wilde

“ I find old men much more interesting than young men,” remarked Charles Kuralt, the docu-journalist when he was asked how he chose the subjects for his reports and commentaries. At this time of year when we reflect on those who have passed from our lives, Kuralt’s words resonate with me. On this Memorial Day I, in particular, am thankful for the old men who have touched my life and made me the richer for their wisdom and friendship.

* * * *

Lester Broughton kept a half dozen bee hives in his yard at the corner of Kelsey and Elizabeth Street and because he had bees, it was inevitable our paths would cross. The spring of 1971 I lived in a townhouse apartment across the street. I would see Mr. Broughton tending his bees from time to time and it was all I could do to keep from crossing the street and asking if I could help. Out of respect for a man at work (perhaps I was a bit on the shy side those days), I would watch the old gentleman but not interfere in his business. It was a swarm of bees that finally connected us. One afternoon I saw the bees issue from one of his hives, become a spinning, swirling vortex of insects, and like a genie from a lamp slowly rise in a cloud. The ball of bees crossed the street, floated up and over the apartment. I rushed out the back and followed them to their new home, a hole in the siding of one of the neighboring houses. As one beekeeper to another, I was duty-bound to inform Mr. Broughton of the loss of his bees. And thus thanks to an errant swarm of bees our friendship began.

“Is the teacher here?” Mr. Broughton would ask my wife whenever he came to call. In all the time I knew Mr. B, I can’t recall him addressing me by any other name than “The Teacher.”And to this day, whether out of respect for an elder man’s wisdom or a commonsense borne of experience, I still refer to Lester as “Mr. Broughton.” (However, to spare the reader redundancy in this post, I’ll make an exception.)

Like most who weathered the Great Depression, Lester emerged thick-skinned, cynical, and where his wallet was concerned especially vigilant. Whether the Depression made him self-sufficient or he was simply “handy” by nature, Les was an accomplished cement man and roofer. His beehives sat on a cement slab intentionally sloped so the bees could light on a grass-free landing pad from which they could crawl quickly to their hive’s entrance. Many of the original sidewalks in Monroe were testimony to his handiwork. The old cement bridge east of Baring on Highway 2 (since replaced) was another of Les’s cement projects. I watched seventy-six year old Mr. B help lay down a hot tar roof on the apartments across from ours, swabbing on the smoking tar in the hot sun alongside men more than half his age. He reroofed his own house, too…up and down the ladder carrying bundles of composition shingles. The Broughtons’ trim little house on Elizabeth Street to this day rests on a stonework foundation and full basement dug by Les himself with, incredible as it seems, the house perched above him as he removed the soil. The dwelling’s chimney and fireplace fashioned from river rock Les crafted as well.

Mr. Broughton was a wood worker (hand crafted his own wooden bee ware), mechanic (and a good one; just ask “Eleanor,”Les’s little lady in black, his demure, gleaming Model A Ford he’d motor about town on special occasions), engineer, gardener (each spring he turned his entire vegetable garden by spade ), woodcutter, beekeeper…and still had time to befriend and mentor “The Teacher” in the apartment across the street.

For eight years I was fortunate to have Les in my life, and I think about him often, especially when I’m tending my bees. When I no longer lived on Mr. B’s street and moved to the country, Les allowed me the use of his honey shed and equipment to harvest my first honey crop from the Valley. And it was Mr. Broughton who helped this clueless soul with the construction of his own honey shed. He showed me how to align the shed foundation with our house. “You want their sides parallel,” Mr. B, the architect, explained. The shed was of prefab construction, and Mr. B saw to it the forms for the slab foundation were square and set exactly to dimension.

The cement man himself was on site the day of the pour. “I brought these,” Les said and produced what appeared to me to be four wooden boxes. When I called in the order, it was Mr. Broughton who told me how much “mud” to ask for. “You’ll have some left over,” he informed me. “We’ll have the remainder poured into these wooden forms and you’ll have yourself some pier blocks when you need ‘em.” Mr. B’s calculations were exact almost to the cupful; those pier blocks did come in handy when I built a grape arbor. Les set bolts in the wet cement for the wall plates.

Whenever I walk on the floor of my shed, I think of Mr. Broughton. The surface, thanks to him, is mirror-smooth. Not a crack or a wave in the cement. “Here,” Les said as he handed me a surfacing trowel. “Now back and forth in a semi-circle arc.” Five minutes later after my floating attempts produced peaks and valleys…no floors, Mr. B said: “Here, let me have that!” I handed over the floating trowel and the shamefaced Teacher stood aside and watched as the master cement man finished the slab. Before he left, Les handed me a roll of tarpaper. “What do I do with this?” I wondered, my thoughts being it was just a bit too early to worry about the roof covering. “Be sure to have your builders layer this between the cement and the wooden wall plates,” he explained. “The moisture barrier will keep your walls from rotting from beneath.”

Anyone experiencing the Great Depression was bound to have a story or two about those days of struggle and Mr. Broughton was no exception. He remembered working in the ice plant on the old Diamond M Dairy site. “We wrapped our feet with gunny sacks,” he recalled, “…couldn’t afford to buy warm boots. “Les related a story about a strange job he had during Prohibition. His assignment was to drive a truck from point A to point B. He was given directions to where the truck was parked, walked to the vehicle, in which he found further instructions on where he was to drive and park the truck. Afoot again, he walked the long way home. “I never asked any questions,” Les remarked, “and once a week I’d find an envelope containing my pay in the mailbox.” When I asked Mr. B what cargo the truck contained, he told me he wasn’t sure, and not wanting to acquire TOO much information, never dared check. “I think I was delivering sugar,” he said, smiled and added “…or corn.”

My favorite Les Broughton story, one I never grew tired of hearing, also concerned the Depression years. To help with the grocery bill Mr. B tended a small flock of chickens which he kept in the backyard coop that later became his honey shed. “Someone was stealing my hens. In those days a chicken made a family a good meal.” The thief would come in the night, snatch a sleeping hen from its roost, and carry it off. “I rigged up an alarm from an old doorbell,” Les said, “ran a wire from the coop to my bedroom. If anyone opened the door, the circuit would close and the bell would ring at my bedside….”

“One night I had just come back from the pool hall and was slipping off my trousers when the bell started ringing. I picked up my 30.06, quietly lifted the bedroom window, fired a round at the shed, and then crawled into bed. The next morning I went out to investigate. The bullet passed through the shed, narrowly missing the roosting hens.” Then Les would begin to chuckle. “I went around back and there scattered helter skelter across the railroad tracks were twenty-seven gunny sacks!”

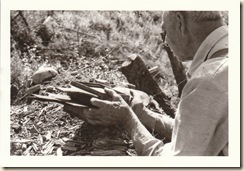

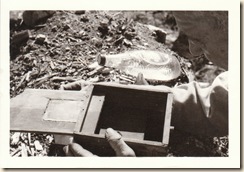

Of the eight short years we were friends, I took only a few photos of Lester Broughton. They were pictures of him at one of his favorite pastimes: messing with bees.

Pearly Everlasting, a fall nectar plant, was in season and there were honeybees foraging the blossoms on Barr Mountain. Les would pluck a bee from a flower, put it in a box with some honeycomb and sugar syrup, and close the lid. Immediately the bee would go to work on the honeycomb, gorging itself on the sugar water. When it was full, the bee flew to the glass window of the box and began buzzing for freedom. When Mr. B slid the lid open, the bee shot off. We noted its “beeline” and moved the box several feet in that direction.

Whenever Mr. Broughton visited our home in the Valley, he would have one request: “Could I have a glass of well water?” he’d ask, which brings to mind another Mr. B anecdote. Once when I visited him on Elizabeth Street, I noticed a garden hose spewing water into the street gutter. “What’s going on there?” I asked my friend. Les replied, “The city charges me a monthly utility fee for water usage, whether I use that much or not.” His water meter showed less than the flat amount for which he was billed monthly. “I paid for it, and I’m going to make sure I use it!” he fumed as the gutter gurgled away.

I can’t walk our place without seeing Mr. Broughton’s legacy, his gifts to me. There’s the huge rhododendron bush, given by Mr. B, at the front of the house (Les started the plant by the “brick method”; he nicked the cambium layer of a branch, pressed it to the soil with a brick until it rooted). Our boxwood hedge separating lawn from garden…a half day’s work to trim each summer… all cuttings Les stared from his boxwood hedge in town. And there’s that smooth cement floor of my honey shed where I’ve extracted a few tons of honey since Mr. Broughton gave it his special finishing touches. The cedar bean poles I used for years Les split for me from a log on his Woods Creek property. He shared his wisdom (“I’m thinking about buying gold as an investment.” Mr. B.: “Gold doesn’t pay interest.”), his time, and his friendship. My daughter was born in 1979. On one of my last visits with Mr. Broughton the summer of that year--Les was bedridden then—he gave me five dollars. “This is for the little girl," he told me, “not for you.” At his word I took his gift and purchased her a savings bond.

There is a belief among beekeepers that when one of us passes, our bees fly away too. I’m not one to say such beliefs are nonsense. Mr. Broughton passed away, July, 1979. The day after his death Les’s wife Fern called to say one of his hives had swarmed. She had no idea where it went, what had happened to it. I did, though. I was certain of where it had gone and that it was in good hands…hands I had shaken in friendship…hands that had known hard labor…hands that loved and worked cement.