Growing peppers and tending a pepper plot are two of my most rewarding tasks in the season’s garden. There is just something about a pepper-laden plant, those pendulous, shiny globes of color and heat, that pleases me. Raising peppers to maturity presents a challenge in our Valley’s short season, maritime climate.

Over the years I’ve perfected my pepper horticulture to the point I now feel confident I can raise a peck of peppers each season, especially the peppers of heat, caliente: jalapeno, serrano, and cayenne. Building on my platform of pepper success, each year I seek a new variety, something exotic to try in the garden. My first departure from the tame (the reliable, thick fleshed California Wonder bell) came years ago when for heat seekers, the habanero was at the fore of pepper popularity. My results, while not stellar, yielded enough of the little “scotch bonnets” to make a batch or two of pepper jelly and a half dozen small jars of “Hotter than a Two-Dollar Pistol” pepper flakes.

One seed catalog featured a variety of pepper called the Peter pepper. When I saw the photo, I knew the Peter had to be that season’s “new to the garden” choice. “What a great gag Christmas gift for the brothers,” I thought, “a pint of pickled Peter peppers for each.” It would be the kind of gift one might find at a Spenser’s Gifts if the store included “naughty” pickled produce among its inventory. As to the choice of names for this pepper variety, I’ll say no more beyond the seed catalog’s disclaimer: “Not for the prudish…” But as the saying goes, “a picture is worth a thousand words,”so with the image provided, let your imagination take you where it will.

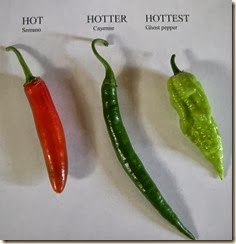

My garden novelty this year is the ghost pepper (Bhut jolokia), a variety native to India; the fruit supposedly was named by the Bhutias people because the pepper’s heat “sneaks up on” those who consume one. In 2007 The Guinness Book of Records entered the ghost pepper as the hottest pepper on earth, a notoriety that assured this indigenous oriental variety an occidental debut. The ghost pepper overheated the previous record holder, the red Savina habanero, to earn top billing for pepper fire.

The agent capsaicin creates a pepper’s heat. The Scoville Scale, devised by American pharmacist Wilbur Scoville in 1912, measures the amount of capsaicin oil a pepper contains.The scale starts at zero with the benign bell pepper (no heat, except what’s needed to bake a stuffed one) and tops out at sixteen million Scoville Heat Units (SHUs) or one hundred per cent capsaicin, a level not found in nature and can be created only in the laboratory. The pepper fancier finds the first real heat in the beautiful, glossy kelly green poblano pepper which weighs in at one thousand to fifteen hundred SHUs.

Whether by accident or gratis, Territorial Seed included an extra seed in the packet. In early March I planted eleven little pips in my indoor seed starter.

“I did a little research,” the peppers’ host told me via email. “The plants grow to a height of three to four feet...width about the same diameter.” (“I planted them too close together,” I fretted.”) My brother continued: “ Ghost pepper fruits take 150 days from setting to maturity.” 150 days? A quick bit of digital calculating told me it would be well into October before the plants produced a mature ghost…and in October it’s not uncommon to get frost here in the Valley. My goal of just one pepper (one ghost, that’s all I hoped for) now seemed a remote possibility at best; I lowered my expectations to the blossom stage…if I could just get them to bloom. But maybe if I doused the plants with Miracle-Gro once a week and our Indian Summer is long and warm, I’ll have some ghosts just in time for Halloween.

Here it is, the latter days of September and I’m reporting in on my “hottest pepper in the world” experiment. At this writing, I’m happy to say the garden gods have smiled on my ghost pepper row. I haven’t counted my yield of “ghosties,” (as my brother calls them), but there must be nearly fifty dangling from the eight plants. To date, none have turned orange or red—the sign of pepper maturity—but several are full term size and, given time, may blush yet. So, you ask, what does one do with the hottest pepper in the world? For the time being, I’m admiring my ghosties and basking in the glow of accomplishment (after all, it’s about the journey, isn’t it?). Some I may use for pepper jelly (there’ll be extra “gag” in the gag gift for the brothers); others I may dry and grind into pepper flakes for woodstove Saturday soup chili; at seventy cents per seed, I most certainly will try to harvest some for myself.

Pride is a dangerous thing, and as the old saw has it, it “goeth before a fall.” I boasted about my “hottest peppers in the world” to my gardener friend Jim. He shot me a quizzical look and said, “I try not to grow anything in my garden that’ll hurt me.”

[Post Script: in 2012 the ghost pepper dropped to second place in pepper heat, replaced by the Trinidad moruga scorpion, besting the ghost pepper by 500K SHUs. I’ve already begun searching for seeds….]